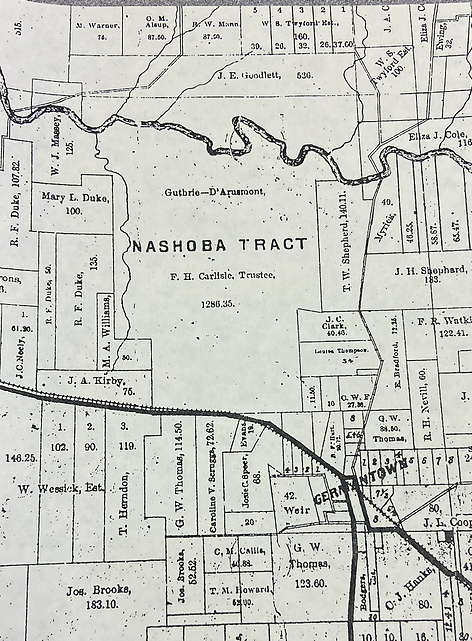

Nashoba

In 1850, Isham Robertson Howze moved his family and all the people he enslaved from Chulahoma, Mississippi to a plantation called Nashoba in Germantown, Shelby County, Tennessee which he rented from Francis Wright. This page is dedicated to the time they spent at Nashoba, their time living with Francis Wright, and some important events that took place during that time. Much of what we know about this 3 year period at Nashoba comes from Isham Howze's journals and some letters written between the Howzes and Frances Wright.

The following is an excerpt from a file I found in the special collections department at the University of Memphis about the history of Nashoba and Fracncis Wright who was a famous writer, abolitionist and feminist from Scotland. I share it here to introduce the reader to Francis Wright and her experimental abolitionist community in Germantown, TN. I’m not sure who wrote this, and I have not fixed any of the errors. The paper simply says: History of Nashoba by Sid Witherington

Francis Wright came from Scotland in the early 1820s to tour the United States and fell in love with the idea of democracy. She wrote a travel book on the United States, the book was the only travel book written before the Civil War by a European that described the United States in a favorable light.

Francis Wright was a close friend to Marquis de Lafayette and she met Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, James Madison, and Andrew Jackson. Jackson helped her find land in Tennessee for her project. Her project was in 1825 to find a way to free the slaves in the South without creating economic chaos. She planned to purchase slaves and let them work to pay off their freedom. In the process she would educate them so they might become a functioning part of society once they were free. When they were ready they would be transferred to various colonies. At this time the National Society of the Colonization of Negroes existed and Jefferson was a member.

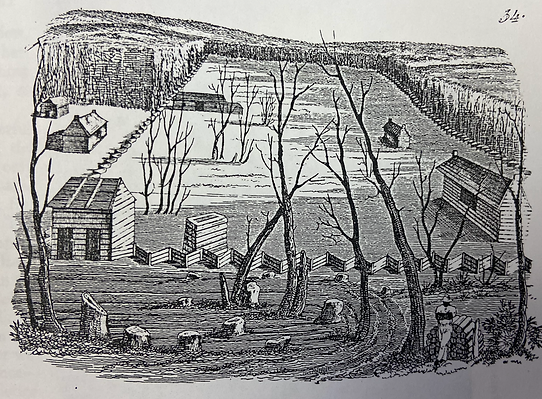

Starting with a few followers and eight slaves, Francis Wright arrived in Germantown to initiate her experimental program. The project ultimately failed because of the harsh climate, hard work, and general ineffectiveness of her followers.

Another development that led to problems for Francis Wright was a letter written by James Richardson, a follower, who advocated that true love does not depend on marriage. This free love concept did not set well with the society of the time. This ideas was not necessarily the view of Francis Wright who was away at the time when the letter was written and sent. Shortly after this incident many of her followers left and financial difficulties prevented her from realizing many of her dreams. The school was unequipped, planned buildings were not started and existing building fell into disrepair. Discouraged, Francis Wright left Nashoba for a editorial job in the North, she became the very first woman editor in the United States.

In 1829 with the help of mayor Winchester she took the 13 adult and 18 children slaves and sent them to Haiti. Later in life Francis Wright embarked on an extensive lecture tour of the country promoting her ideas on women’s rights, education, religion, and labor, most of which were controversial ever for modern times.

In December 1850, Isham Howze traveled from his home in Chulahoma, Mississippi up to Shelby County, Tennessee. He arrived at the home of Dr. Thomas H. Todd in Germantown on December 13, 1850. Dr. Todd was the second husband of Isham’s sister Francis Howze Roper. After Francis died, Dr. Todd married her daughter (his step-daughter), Burchet Roper. Dr. Todd had a friendship with his neighbor Francis Wright, and it is likely that Dr. Todd is the one that recommended Isham consider renting her property at Nashoba.

Howze’s diary (Book 6) includes his retelling of the details of this trip. Where there are blanks in my transcription, it is because I could not make out the handwriting there.

Friday 13th arrived at Dr. Thomas H. Todd’s. Saturday 14th visit with Fanny Wright and examined her farm and I with a view of enjoying to live there next year. Returning the evening to the Doctor’s and through him ____a ____ to take Mrs. W’s farm. She retains one room in her new house as her own and will board with me. I take possession of all her stock of every description, and use it as my own, returning as much (____) when I leave. The same in regards to corn fodder, farming tools, wagons and everything I require without ___ for ___. In addition, she furnished the farm’s two hands---negro men---for which with the use of the land, I am to pay a reasonable hire or rent to be discharged by boarding her and her ___ house. Attentions of servants, in serving, working, etc. and in the improvements of the houses and farm. All of which Dr. T is to divide after. If my improvements fall under, I am to pay her the difference. If they go over, she is to pay me. The improvements as to what they are to be are to be decided upon, by the parties concerned. We made no written bargain, but Dr. Todd understood the whole matter, and will decide, if ___. Remained at the Dr. till the evening of Monday the 16th. Came that evening to Mrs. Blocker’s –next evening returned home. Evening of the 18th (Wednesday), Miss Fanny Wright’s wagon came for a load of my affairs. Today, Thursday 19th the wagon is here. I am to start back tomorrow. Thus, for in d_ upon divine providence, I have made arrangements for the next year. And may the Lord smile upon my efforts.

Once the deal had been brokered regarding Nashoba, Isham begins to move his family, his “servants”, and all his belongings via multiple wagon trips over about a week’s time. He writes:

Friday 20th Started the wagon back to Shelby this morning between 8 and 9 o’clock. Sent son Ady and Sarah and Child and Jerry and two cows and ___. I trust all will go safely and comfortably. ___ late evening to Ms. Fanny and Dr. Todd and sent the letters today by son Ady. I shall report him back with the same wagon in eight or ten days or in __ time.

Sarah is Alcorn’s aunt, and Isham’s “servant”. We will learn later that Sarah’s child is named Rachel. I believe she was born around 1842 in Chulahoma, Mississippi but I have not been able to determine who her father was. Isham continues:

Friday 27 Dec. Son Adrian returned from Shelby, with Ms. F W’s wagon accompanied

with Dr. JR Todd’s wagon __ and on Saturday 28th sister Martha, son Ady, and servants Fanny, Aggy, and Nathan and myself left Chulahoma for Shelby and on Monday night the 30th Dec. we all arrived in safety at Nashoba, the residence of Ms. Wright. And now Tuesday, the last day of the year 1850 I am here (Nashoba). Thus far the Lord has been with me, and I believe he will not forsake me. I have put my trust in him and will confide in him as long as I live. On the 30th of Dec 1830 I arrived in Lincoln County, Tenn from Alabama and 20 years to a day afterwards I return to Tenn to live again. This is remarkable, how long I may remain here God only knows.

While they were living in Nashoba, Elizabeth gave birth to their seventh and final child named Isham Roberson Howze, Jr. after his father. In his diaries, Isham, Sr. often referred to his youngest son as “Ike”. The home at Nashoba where they lived must have had several rooms as they were now a very large family—Isham and Elizabeth and their seven children ranging in age from 18 years (Adrian) to the newborn (Ike), as well as Isham’s oldest sister Martha Duke Murray and, of course, Francis Wright who owned the property and boarded with them in exchange for the use of the tools, land, buildings, and the two “negro” farm hands.

In addition to the white folks, there were also the following Black Howzes they enslaved: Aggy, Jerry, Sarah, Rachel (Sarah’s daughter), and Nathan who were considered the property of Martha Murray, and Grace and Dilcy the two older women Isham’s father willed to him upon his death. I don’t know how or when “servant” Fanny mentioned in the previous diary excerpt entered the picture, but we know she is there too by Isham’s diaries. She is Rev. Alcorn's cousin and you can learn more about her on the "Cousin Fannie" page on this site.

It is unclear to me if the Black Howzes had their own cabin or if everyone was under the same roof. This rendering of Nashoba shows several buildings, some of which may be barns for their livestock, some may be “slave quarters”.

Whether there were eleven people (just the white ones), or nineteen (white and Black), Isham’s diary indicates it was a very busy and noisy home for them.

Near the beginning of May 1851, while living in Nashoba he wrote:

In somethings—and important ones too—I am dependent upon others. Many of my important advantages are derived from two sources—my good sister, and the friend in whose house I live. They are truly my friends. They have both been unfortunate and are unhappy. I would wipe any tear from their eyes if I could and render their lives happy were it in my power. But I cannot. They both as well as myself require something which I cannot furnish them—peace and quiet. For the time present, I hope I am useful to them both. But I would be more so if I could. I would place them in more quiet circumstance. But how to do so I know not. It seems best now, under my circumstances, that we should remain together. Another building or suit of buildings for the purpose of quiet to them mean these would make all this more agreeable. But the buildings, for them, or for my own family, we do not have, nor have any others the means at present to procure them. God knows how cramped it is full and how I would reserve every embarrassment if I could.

Isham doesn’t write much in his diaries about the work they did at Nashoba during the first year as tenants, but it doesn’t sound like he was able to fulfill his side of the bargain with Francis Wright. In December of 1851 – a year after their first contract was negotiated, Francis Wright had moved to Cincinnati Ohio. Some transcripts of their correspondences are located at the University of Memphis Library special collections department.

Below is a transcript of Francis Wright’s letter to Isham Howze regarding the Nashoba estate lease agreement which seems to indicate that the first year of the arrangement did not go as planned. She wrote:

Proposal wch fr Tho. H. Todd is authorized to make to Mr. Howze from Frances Wright.

Frances Wright will pass a sponge over the debt of the past year with the exception of the dining room wch Mr. Howze shall build neatly and conveniently on the north side of the present house between it and the kitchen.

She would cede to him the mules, wagons, stock, tools, implements and all upon the same premises for the sum of five hundred dollars. One third of said sum to be paid down and the remainder on the first of January 1853.

She will rent to him the place for the coming year at $2.50 per acre. The same to be paid in labor that shall be of permanent benefit to the place or in money. He also being pledged for the care of the whole estate with the timber upon it.

If the above proposition be not accepted then Mr. Howze shall be bound for the legal rent of the land during the past year, he having failed to his promises with regard to the rent in services and return of corn and meat, etc. And then also fr Tho H Todd shall dispose of all the movables on the place at public sale and rent out the farm to a responsible and suitable tenant.

Frances Wright

8th of Dec. 1851

We know that Isham and his family continue to live at Nashoba through December of 1853, so he must have accepted this offer to wipe away his debt from the first year. I am not certain, but I believe he also may have paid the $500 to Francis Wright for the mules, wagons, and other farm implements.

According to the inventory of stock, tools, and implements also in this collection in the same collection, we learn that Isham and his family were responsible for 3 mules, 1 mare, 4 cows and 3 yearling heifers, 1 fine male 3 years old of the white cow, 18 large swine about half of them sows, 46 pigs, geese and ducks.

The tools and implements include axes, planes, scythes, knives, hoes, as well as some larger items like a two-horse plough, 3 turning ploughs, 1 large heavy harrow, 1 large wagon with 4 pair of harness, 1 small wagon, and some saddles.

Despite what appears to be a rather strained landlord-tenant relationship between Francis Wright and the Howzes, it does seem that for Elizabeth Howze, at least, there were feelings of friendship and closeness towards Wright. There are a few letters from the Howzes to Francis that provide a great deal of information about their life at Nashoba. The letters also solved a mystery found in Isham’s diary entry from July 17, 1851.

In his diary, Isham tells us that Jerry (Rev. Alcorn's uncle) left Nashoba without permission or forewarning and took one of the mules. Isham doesn’t seem to know what instigated his departure, but he seems to think he knows where Jerry will go. He also reveals more about his own views about the institution of slavery in general in his reflection. He wrote:

I own my imperfections. I feel my weaknesses. I am inferior. Or in other words, feel my

total inability to ___ with the world as it now is with my poor capacity of mind and body. Every day I become less and less able to endure and nearly every day I meet with new trials. Negro boy Jerry, took a mule last night and went off I presume to Lincoln County in this state. This, in him, to me was wicked. He has been placed under my control, and I could do no other than keep her here with me. I treated him as tenderly as I do my own children—and yet he has left me and left me in bad circumstances. He has stolen the mule and left me. If ever I get him or the mule—which is quite doubtful, much expense will be incurred, and I am ill able to bear it. But so it is, and I beseech the Lord to guard me from sinning about it. I have felt indignant, and I fear have spoken wickedly. Would to God I could have nothing to do with slavery. Not that I believe it is sinful under any circumstances no, I do not. To the African race I believe in the providence of God. It has been a blessing, but I am not of the right temperament to be a slave owner: I am not rigid enough in my discipline. But I will say no more. God rules and all his ways are just and true. And every event will work for good to them that love God. While on the other hand everything will work for evil to them who do not love him. If I know my own heart, I do love God. Hence, I believe everything will work for my good. I have written to the Sheriffs or jailers of Fayette, Hardeman, McNairy, Hardin, Wayne, La___?, and Giles counties and to JW Hill and J N Hayes, Petersburg, describing the boy and mule. May the Lord’s will be done and may I be made subservient to it is my ___.

Isham never writes again in his diary about what happened to Jerry. He never explains where he went or when and how he returned home—for Jerry is back with Isham’s family in the next journal and mentioned casually as if he had never left. The letters between the Howzes and Francis Wright solved that mystery for us.

On August 10, 1851, just a month after Jerry left Nashoba, Isham wrote a letter to Francis Wright in which he reports, “We have heard of Jerry and mule Sal. He arrived at my old neighborhood in Middle Tennessee in five days after they left. I will get the negro and mule again”. And, as if using Jerry’s departure as an excuse for this failure to deliver on his promises, he writes “We still have gloomy prospects as to crops –not enough rain yet—I have had bad luck. Jerry has disarrayed my plans exceedingly, but I will do the best I can and all I can, for you and for myself and hope for the best.”

I would really love to know why Jerry left when he did and why he went back to their old neighborhood in Middle Tennessee. Why did Isham assume this is where he would be? I don’t know the answers, but I have a theory. I think Jerry went back to Middle Tennessee to visit someone he knew and loved.

He may have gone back to visit family members that were left behind when Isham moved away from Lincoln County to Chulahoma. There were likely many others, but we know that when William Duke Howze died in 1849, he left two of his slaves, Henry and Milly, to his daughter Amy. I believe Henry was Jerry’s uncle and Milly was Henry’s wife, but I am not 100 percent sure.

When Jerry ran away with the mule to middle Tennessee in 1851, he was around 29 years old, and the only white Howze relative living there was Amy Howze Campbell, Isham’s sister and the widow of Parker Campbell. Amy was blind and bedridden at this point in her life and would die in just a few more years. I wonder if Jerry was concerned that someone he loved—maybe Henry, or a sibling, or perhaps even his own father—would be sold away if she were to die.

Another possibility is that Jerry was going to visit his wife. Like my other speculations about this, I really do not know what happened. However, I do know a few things that could make this theory plausible. Jerry’s wife, we learn later, is Mary Wilson. I believe that she was enslaved by Elizabeth Wilson Howze’s family for most if not all her life or was purchased by them at Jerry’s request.

We may never know the real reasons, but what we do know is that Isham brought him back to Nashoba—almost an entire year later. This is one of the reasons that I feel it may be likely Jerry was there to be with his wife (or future wife). I can imagine that if this was the reason for his leaving, that Isham would have been more willing to let him stay so long—or at least not try to go and get him immediately. We know that Isham did not like that slavery (really, enslavers) separated families, and we know that he assumed Jerry went back to Petersburg—perhaps because he knew that Mary was still there.

We know that Isham went to get Jerry after about a year of him being away, because of a letter written by Elizabeth Howze to Fanny Wright in August 1852. I have included several excerpts of her letter, because it is unusual to have this level of insight into the lives of these people, interesting to get a sense of the familiarity and friendship between two women at this time, and most importantly because it sheds light on the lives of the people the Howzes enslaved.

Nashoba August 22, 1852

Miss Fanny, Dear friend,

I have delayed long in writing to you, but many reasons could render which I know you would receive but will not tax your patience with them now. We have waited long to hear from you […] When you left you promised to return this year and spend some time with us. We would be happy to see you, and do come—the change would help you.

Mr. H’s health has been very feeble all year—albut seldom able to perform any kind of labor. Adrian and Will, poor fellows, have labored hard with their crop and chills together. But they have waded through, and feel that their efforts have been bountifully blessed. The crop of wheat yielded about 100 bushels – pretty fair crop of oats […].

We now have all the hogs, cows, and horses on the wheat pasture—doing finely – I have but a small supply of milk and butter though as I milk but two cows and they have nearly gone dry. The large brindle and old blue cow died last winter – all the rest look well. The horses all alive—the cats alive except Tom – Coon, as affectionate and sensible as ever. Opossum’s three last kittens I gave to the Dr. […]

The servants all well. Mr. H brought Jerry back, who has behaved very well since. Says he never will do so any more.

A journal entry in his diary from October 31, 1852, tells of a trip Isham took from Nashoba to middle Tennessee. He does not mention Jerry or the reason for his trip, but I think this trip was significant, even if it wasn’t the trip when he went to retrieve Jerry.

Oct. 31,1852. Sunday. I am once more at home. I left home on Tuesday the 21st of September, in company with G. D. Campbell and wife and my son Henry, for Middle Tennessee. Arrived at J. W. Hill's, Lincoln County, 8 1/2 o'clock, 28th same month. Remained there until the 18th of October, and came as far as Sister Campbell's. Next day, 19th, started home via Fayetteville, and arrived at home Friday the 29th. John Hill and his family, and my sister Martha, came with me and my son. We stayed with the wagon till we all passed Purdy, where we (the white ones, except Mr. Epps Mr. Hill's waggoner) left them - Epps and Mr. Hill's negroes. They went to Chulahoma. Mr. Hill and my son William started there- Chulahoma- this morning.

Other important events that happened while they lived at Nashoba

There are several other important events that happened during the Howze’s brief time at Nashoba including the death of Francis Wright. Isham wrote in his diary on the day he learned of her death while he was away from Nashoba down in Desoto County, Mississippi:

Wednesday evening December 22nd, 1852. At Mr. A. Stewart's in DeSoto county Mississippi. Heard this morning at home of the death of Miss Wright. My neighbor Mr. Duke brought me over a paper --The Eagle and Inquirer—one of the Memphis dailies containing the announcement. She died in Cincinnati OH on Monday the 13th. Poor woman! She now knows whether or not her sentiments in regard to religion are true. But she was a good woman in many respects, and I am truly sorry to hear that she is dead. She has been good to me, and I lament her death. She is gone and may she be happy.

Months later, in April of the following year, he writes again about his friend Fanny:

I have been reading of late some of Fanny Wright’s speculations; ingenious speculations they are. She says many true things which would be well for mankind to observe. But, oh, her scheme has no soul in it – no vitality! It is as cold to me as the polar ice would be to an inhabitant of the equator. She has no god in it, but as an abstract principle. Strange that such a mind should be satisfied with such an unsubstantial system. How is it? Will so much excellence as she surely did have meet with no reward? She is in His hands, whose existence and merits she disowned. And he will do with her as he will. Here I leave her. It is not for me to say what she will be. I had respect for her virtues while she lived, and can but hope that Jesus was her savior. She fed the hungry and clothes the naked, and had a benevolent heart, and aimed well. Btu she did not believe in Jesus and do good in His name and for him. But Jesus had mercy on the dying, thief and he may have had mercy upon her.

And a little further down in his diary, again he reflects upon the fate of Fanny after her death:

I am no apologist for Frances Wright d’Arusmont, for her course in life did not meet with my approbation. She stepped out of the sphere of woman into that of man; and besides, her sentiments were, in my humble opinion, religiously and socially wrong. But from a close acquaintance with, as a member in my family for some six months, I think I can safely say that she meant well. Though an unbeliever in the Christian system, her charities were expansive, and real Christians might have learned a good lesson from her example. She was good to the poor – without ostentation. Her good deeds were done in secret. I can but hope that she is in a better world than the one she has left. I can but hope that she turned from her errors and was accepted by her Lord. She loved much, and in my opinion, she acted the Christian better by far than many who have had the reputation of great piety. She had her failings, and there were many, and her chief one was her denial of her creator and redeemer. But who can say that she had but been on the lord’s side!

I wish we could know what Alcorn’s family thought of Francis Wright. Jerry, Nathan, Sarah, Aggy and the others knew her. They lived with her. They likely saw her wearing her famous—and extremely scandalous for the time—clothing. Her usual attire was described as “a loose, long sleeved tunic of some very fine material, bound at the waist with a flowing sash and reaching only to the knee; and below it a pair of Turkish trousers”. I wonder what they thought of her trousers.

I wonder if they knew she was an abolitionist. Did they overhear her and the white Howzes discussing social and political issues? Did she talk about those things with them? As an abolitionist who wanted to end slavery in the United States, who purchased slaves to free them, what did she think of renting Nashoba to an enslaver? She doesn’t seem like the kind of woman who would have kept her feelings and thoughts about this a secret from her roommates! Unfortunately, I don’t know the answers to these questions.

A second significant event that happened while they were living at Nashoba was the building of the Germantown Presbyterian Church in 1850. While Isham was a deeply religious man and wrote thousands of pages in his diaries about his faith, he very rarely attended religious services on Sundays. He always seemed to be more in line with Baptist theology, but his wife and several of his children were Presbyterian. While living at Nashoba, we know from Isham’s diaries that his family attended preaching and religious meetings quite often. On October 2, 1853, he writes that:

"Henry and James are here with me, all the rest of my white family, and some of the servants have gone to meeting. Sister Martha being at Doctor Todd’s. I trust those who are at church may be benefited by the services of the day. It is, I suppose their communion day."

I don’t know which servants attended church with the white Howzes, but it’s fascinating to know that some of them did. Even more incredible, is that the original church building from 1850 was the only building in Germantown that survived the Civil War. The same building where Alcorn’s family—perhaps his own father—would have attended in 1853 is still standing in Germantown Tennessee today.

A third significant event that happened during the time they were living at Nashoba was the construction of the Memphis and Charleston Railroad through Germantown in 1852. Isham speaks about the railroad as a dangerous but exciting invention of progress several times in his diary. This would be the first time that passenger trains would be available in such close proximity to his residence. We don’t know what Alcorn’s family would have thought about the trains, but we do know that some of them were able to ride! Isham wrote this entry in July of 1853:

After early breakfast, sister Martha and I went up to Germantown, intending to take the cars for LaGrange, but we concluded not to go. I could not get a seat in a passenger car, and I felt too feeble to go in an open car exposed to the sun, etc.… Son Ady and servants Nathan and Jerry went. After dinner. One train of cars has returned already and passed on toward Memphis. Two others are yet behind, by which I presume most of the company that went up will return. The first train must have left Lagrange by, or before 12 o clock. That was the regular mail train.

Not long before their time at Nashoba would end, Isham took several prospecting trips down to Wall Hill in Marshall County, Mississippi to look for land and a home to purchase. He ultimately decided to purchase land next to his wife’s family and enter into business with Mr. Brady and Mr. Pace to open a store that would be built by Mr. Wall (for whom the village was named).

Before they commence to move, however, there is another interesting journal entry about Jerry. One night, the family entertained a Mr. Evans who stayed a few hours and joined them for dinner. Isham writes that Mr. Evans “left for Germantown to preach for the negroes”. That same night, he says, “Jerry, the servant, just now killed a large rattlesnake not far from our yard. 4 ½ feet long, 6 inches in circumference, 6 rattles and a button, a frightful looking monster.”

Throughout November and December of 1853, Isham moved himself and much of their belongings to their new home in Wall Hill. Elizabeth and the younger children were still in Nashoba and Nathan was tasked with driving the wagon back and forth, moving furniture, food, and other items, and he would also deliver letters back and forth between Isham and Elizabeth.

Here are some interesting details of the move from Isham’s diary which I share because they tell us much about what Nathan was doing and was responsible for during the move.

Left home on Tuesday last, the 22nd. Adrian and Nathan (in the wagon) with me. Went that day to Dr. Hayes’ Byhalia.

Wednesday 23rd to Dr. Wilsons where we left our wagon and its load and Nathan and Adrian and myself went to James Wilson’s.

Friday evening 25 we all left for home. Ady and Nathan (with the wagon and 3 bales cotton for Mr. Allen, to be sent from Germantown to Memphis) from Dr. Wilsons.

Ady and Nathan camped out and arrived at home Saturday afternoon 26th. Wm and myself stayed at Dr. Hayes and arrive home Sun. after Ady.

29 Nov. Tuesday noon – Just now started Nathan and the wagon for the “Black Jacks” my new home that is to be. I shall not go this (the second) time, but shall send my boys Adrian and Wm. Charlotte also goes. My rye and wheat will be sowed and after that Charlotte will remain in Dr. Wilson’s service till we shall need her. The others will return after my grain is plowed in. …. My boys will go in the carry all- taking some things with them. My writing desk, and the top of my little bookcase and will start this evening.

A “carry-all” was a type of horse-drawn wagon or carriage that was commonly used for hauling things. It may or may not have had a wood framed cover. I also want to point out the mention of “Charlotte” in the previous excerpt. You can read more about Charlotte on the the page dedicated to her on this site.

Same day, abt ¼ after 2 o’clock. My boys left for Mississippi in the carryall, working my mare Potomac for the first time in that carriage since I have been here. She worked well as she left, and my sincere prayer is that my boys may go and return safely…

December 10, ¼ to 12. Nathan returned with the wagon: the boys, Adrian and William, still behind. Nathan could give no account of them, only that they told him when he left evening before last that they would overtake him before he would get home. He says that all went well except Mary Wilson, and she was on the mend. Thank the Lord. They had sowed my grain and hauled home some corn. But for particulars, I will wait for the boys to return. They will in all probability be home this evening. Nathan says he brought a load of Cotton, 4 bales to Germantown for John Campbell.

I find it very interesting that Nathan is said to be driving the wagon alone here and that he was asked to carry a load of cotton for John Campbell from Mississippi. The way it is written, it seems that Nathan notified Isham of this detour rather than Isham approving it ahead of time.

Adrian came home between 4 and 5. Wm remained behind. Potomac strayed off from Mr. Wilsons’ the night before and Adrian had to borrow a mule from his grandpa to ride home. He came all the way today. Left Wm to hunt up his mare and come home as soon as he could get here. If he could get here at all with the carryall.

Dec. 12 1853- Monday night after supper….I have felt badly all day, though I have done for me, a hard days work in packing and loading the wagon to start on my third trip, morning will send Nathan and Henry and James, Adrian will remain here. Wm has not returned yet. I fear Potomac has strayed off entirely so that I shall never get her more.

13 Dec. … My wagon started this morning as I calculated I should. My boys, James and Henry went with Nathan. “Indian Summer today” a dark day. Somewhat cloudy.

15 Dec. Thursday morning…It rained nearly all day yesterday and it is yet cloudy and very damp, but not raining. …Son Wm came home yesterday about 4 in the evening. Left his grandpas in the morning. He found Potomac somewhere up there at a Mr. Coleman’s I believe, near Mr. Wilson’s. I am thankful that she is found, and that Wm has come home.

Dec. 20, 1853 - Sister M went home with Dr. Todd yesterday to return no more till we move away. Some of her goods are in the wagon and the wagon is now nearly ready to start again. I shall send James and let him remain up there, and let Nathan return alone. I shall send Aunt Dilcy too to remain.

Again, we see an instance where Nathan is trusted to drive the wagon alone. Dilcy is mentioned as well here. She is Nathan’s aunt and one of the people that Isham has enslaved. Later that same day he wrote:

The wagon is gone. Nathan is the driver. Dilcy and my son James went to remain. This is my fourth Load.

Dec 25, 1853, at Wall Hill - it’s exceedingly cold. The snow is deep and not melting away. Fires on hand to keep—the house is full—some of my chattels in addition to all of them of Dr. W’s family.

Most of the time when Isham uses the term “chattels” in his diaries, he seems to be referring to his physical belongings such as furniture, trunks, etc. In this case, I think he is specifically referring to the people he enslaved, and those that “Dr. W” (Elizabeth’s brother, Dr. Wilson) enslaved as well. He wrote this on Christmas Day, 1853—that the house was full, some of his “slaves” and all of Dr. Wilson’s “slaves” were there together.

I don’t have a sense for what Christmas would have looked like for Alcorn’s family in the 1850s—whether they would have been allowed to have a day of rest, whether they would be included in or excluded from the white family’s traditions or not. There is one reference in the diaries to their celebration of Thanksgiving in 1856 which may give us a clue. Isham wrote on November 20:

“This has been Thanksgiving Day – a proclamation of the governor of this state (Miss) John J. McRay (I believe is his given name). I have tried to observe it. All the working hands had rest from the usual labors”.

So, perhaps it is possible that Alcorn’s family had a bit more time off than a typical day on December 25, 1853.

Although, it’s also possible that the opposite is true, and they were made to work even harder on that day to ensure that the white family had a nice celebration. In “History of a Southern Presbyterian Family” a book written by Elizabeth Howze’s brother, Legrand J. Wilson, we learn that all the Wilson children and grandchildren came to their parents’ house on Christmas Eve. He writes,

Once a year, on Christmastide, they had to meet and spend, at least, one day and night with grandpa and grandma. It was the yearly picnic for the family, and all made an effort to be on hand on the evening of the 24th. The children came, and the grandchildren came, and I wondered often how they would take care of the crowd, but that never bothered her for a moment, and she would not only take care of them, and make them comfortable, but would fill them with the sweetest of good things, even after her health gave way, and she was almost an invalid (pg 86)

This information, combined with the remark from Isham’s journal that he and his “chattel” were at Dr. Wilson’s makes me think that they were actually there to work more than to rest.

On December 29-30, 1853, Isham writes about one final important conversation he had with Nathan before they moved to Mississippi. It is heartbreaking and infuriating to read but it is one of the most personal tidbits of information about Nathan in all of the journals.

I have written to my wife this morning, to send by Nathan tomorrow.

Dec. 30 Friday Morning. Nathan starts home this morning with the wagon. It rained considerably last night and is yet cloudy and likely for more rain. I call Nashoba “home” because my wife and most of my children are there yet. And when they are as their home, then is my home for they are my joy.

Nathan has gone. Before he left he called me out and asked me to hire him out in Shelby County: his object is, or was, to get married there. He has known for a long time, that I would not hire him in Shelby longer than this year and that I was coming here. Hence, he has acted imprudently in engaging to marry. Though I have no objection to his getting married—and would rather he would get him a wife, if he desires to have one, for marriage is honorable.

But as the relation of master and servant is now constituted it would not do for him to have a wife so far from home and I cannot think of hiring him out—especially in another state so far from home. I am sorry for him, but I cannot help him. He is not mine (only as trustee) and I cannot sell him, nor am I able to buy the woman he wishes to marry. So, this evil of slavery he will, of necessity, have to hear. I cannot remedy it. It is an evil, the family relation, and the greatest evil in the institution.

The evil is in this—wives and husbands, parents and children etc. can be separated according to the will of the master. If this could be avoided, slavery would be a small evil if indeed it would be an evil at all.

Slavery in some form or another has existed from the earliest periods of time. And it has been sanctioned by divine authority under the new as well as the old dispensation. There even has been inequality in man’s condition. In intellect and station in power to govern and in everything. It is all nonsense to talk of equality. Some creatures are and must be greater than others. Some men by nature, or constitution, and qualified to govern and other to be governed. I am sure that I have superiors as well as inferiors and the station I occupy is the best for me. And I believe providence places every human being in the station which suits him best. But enough! I would if I could gratify Nathan, but it is out of my power.

Nathan did not get hired out in Shelby County. Isham had his way and moved Nathan and everyone else down to Wall Hill, Mississippi as planned. Whoever it was that Nathan wanted to marry; we may never know. I wonder if Nathan ever told anyone in his family that he had wanted to marry a woman from Shelby County. This is the only reference I have found about his desire to marry.

For a while after this conversation happened between them, Nathan continued to drive the wagon between Nashoba and Wall Hill carrying crops, people, furniture, and letters written between Isham and Elizabeth and driving cattle occasionally. The weather was very cold and wet that first week of January. Isham’s diary entries from January 7, 1854, tells us some of what Nathan experienced.

January 7, 1854, Saturday morning. The ground is covered over several inches in fine hail, and it is yet hailing fast while it is very cold indeed. Nathan returned home last night with his load of cotton and here he must remain till better weather.

Evening- It has been hailing and sticking all day. Nathan is still here.

My trials are great. I love my wife. I love my children. I love my sister. I am the nominal head of my family. I love our servants and they too are scattered and divided. It hurts me to see them exposed and to know that they suffer. Those of us here, for good, are safely found, though the servant’s room is open and cold. Poor Nathan has had a hard task, going and coming with the wagon. Others behind, white and black have to come through the cold and wet. Stock to be driven, children exposed, wife to suffer in mind as well as in body. My sister, too, poor weakly creature, but she can remain behind till good weather. The others must come if they can.

By January 14, 1854, the move to Wall Hill, MS from Nashoba, TN was finally complete.