Civil War in Wall Hill, MS

This page is dedicated to sharing information about what was happening in and around Wall Hill, MS during the Civil War. Wall Hill is where Alcorn's family was enslaved by Isham Howze.

Rev. J.A. Alcorn was born after the American Civil War but most of his family lived through it. Unfortunately, I could not find any records or other information about what they specifically experienced during the Civil War because so few records about the lives of Black folks during the civil war exist. The diaries of their enslaver end in the middle of 1857 when he dies, so they are no longer a source of information either. It would have been a very serious event in their lives when the head of household and former enslaver died. I assume that Nathan, Jerry, Sarah, Rachel and Aggy—who were willed to Isham by his father to be held by him as “trustee” for Martha—would immediately be transferred to Martha upon Isham’s death. We know that they are in her household in 1860 according to that year’s “slave schedule”.

Isham Howze's obituary in the Tennessee Baptist newspaper, Saturday October 3, 1857, gives us some information about the time leading up to Isham’s death.

We know from Isham's journals that Nathan (Alcorn's father) was very frequently tasked with driving people and farm products in the Howze's wagon. When I read this obituary, I think of Nathan and that he would have likely been tasked with driving Isham from Wall Hill to Dr. Todd’s in Germantown, TN while Isham was extremely ill. I think he may also have been tasked with driving Elizabeth and the children back and forth much like he did during their move from that place in the winter of 1853. I imagine that Nathan was probably also responsible for carrying Isham’s coffin back to Mississippi, because we know that Isham was buried in Wall Hill, in the family cemetery near the southwest corner of their property.

I have compiled some information about what was happening in Wall Hill and in the surrounding areas before, during, and just after the war. I want to know what Nathan and the others’ lives might have been like. So, in the absence of records on the subject, I have cast a wide net thinking that some of what I learned about this period would have been known, understood, and/or experienced by this family.

A note from Emily: I have never been one to care much about what white people were doing during the Civil War. I am not one of those people who remembers names and dates of battles, and I have never intentionally visited a Civil War battle site. I’m just not that into it. If the reader is hoping for in-depth analysis of the war, or any sort of enlightened interpretation of its events on this page, they will be disappointed. I am simply sharing a few small details that might shed some light on what life was like for Nathan and his family during this period. Unfortunately, that means relying on the stories, memories, and sometimes all-out fabrications of white people. I hope the reader will read them with a healthy dose of skepticism, as I do, while still allowing it to spark your imagination about life for this enslaved family during the war that would eventually bring their freedom.

The white Howzes and the Wilsons were from North Carolina and Virginia originally. They were slave owners, but generally against the idea of secession. Isham writes about that in his diaries some—that he is not for abolition, but he is also not for cessation. Apparently, this was how his father-in-law felt as well. LeGrand J. Wilson writes in his book, History of a Southern Presbyterian Family, about his father:

…as the war clouds began to rise in the Northern sky, and secession whispered in the

South, he took a strong, uncompromising stand for the Union. He believed that secession would produce a long, bloody war. But when his State in convention passed unanimously the ordinance of secession, his mouth was closed, and I never heard him murmur or speak a harsh word against the North, until the General Assembly, in 1861, in Philadelphia, refused to receive the Southern delegates, and branded them as traitors, heretics, and schismatics. This was too much for the Camel’s back, and he was converted, and nothing but the weight of threescore years and ten kept him at home.

I guess he wasn’t “uncompromising” after all. Although Isham was dead by then, I think this is how he and Elizabeth and all of their children likely felt about the war—against it until it happened then they were full supporters. All of Elizabeth’s eligible sons went to fight and many of her brothers did as well.

LeGrand J. Wilson’s book “History of a Southern Presbyterian Family” is a personal memoir, full of his fond (even if not entirely accurate) remembrances of times past. The book was written in 1900 at the height of the southern “Lost Cause” campaigns to revere the rewritten history of the Confederacy. Despite that, his is the only book I could find that talks about what life might have been like during the war precisely in the neighborhood of Wall Hill where Nathan and his family were living. I hope the reader will keep in mind that it is problematic while reading the following excerpts.

My father lived ten years longer, and four of these were years of trial and sorrow. War was in the land. His children and grandchildren were called to the service of their country, and he was kept at home by the weight of threescore years and ten. But he was strong and vigorous, and was more useful to his children and grandchildren, than in any for years of his life. He kept the old homestead, and had his two youngest sons’ wives to care for, with the little ones, while they were fighting for their country. He kept up his farming, raising corn, meat, potatoes, peas, etc., but very little cotton. And succeeded in feeding and clothing the negroes, and his little household; although the Federal Cavalry, two or three times, stripped him of everything in the shape of food. The negroes were faithful, and would run off the stock and save them from the raiders, but it required eternal vigilance. The people had a system of signaling, that was really interesting and very effective, and saved them a great deal.

A raid would start from Memphis. As soon as the people could ascertain which road it would take, a horn would blow, and it would be taken up and down the line on that road, and in thirty minutes the people would be warned for twenty or thirty miles. Negroes were very faithful and never failed to hear the signal at night. This gave the people time to hide their provisions and their stock. (pg 85-86)

We learn a few other details about Civil War time in Wall Hill from LeGrand J Wilson’s other book, “The Confederate Soldier” which was written around 1900, also during the height of the Lost Cause campaigns of the early 20th century. Every time he mentions something done using passive voice, that tells me that a human person—likely a slave of his family—was made to do that thing. For example, “a ham must be boiled” likely means that an enslaved woman had to boil a ham. Keeping that in mind while reading lines helps us realize that when the person acting upon the subject is not mentioned, we may be seeing shadows of an enslaved person—someone who was either related to Nathan or someone he likely knew very well.

I shall never forget the 9th day of July, 1861. My company was ordered to meet at Wall Hill, a village in the western part of Marshall county, Miss., to start to Iuka, Miss., to be equipped, drilled and prepared for service. The 8th was a busy day at my father’s, and a hundred other homes in the surrounding country, getting everything ready for the young soldiers.

We were ordered to carry a week’s rations from home. A ham must be boiled, bread baked, a quantity of coffee parched and ground, sugar, preserves, pickles, cakes, et al., a large box full was prepared; and my father had a barrel of kraut made that the boys might have some vegetable food while in camp, for we expected to remain in Iuka about two months. […] My old Nurse Rose rolled up a lounge feather bed, blankets, pillows, etc., and I really had more baggage than the entire company possessed six months later on. […]

Night passed away, morning came, and after breakfast all were called in to prayers. My dear old father 70 years of age, read the 90th Psalm and tried to pray. I know that my prayer was partly answered, for I am still here. Shaking hands with the servants, we rode over to Wall Hill, where we met the entire neighborhood—fathers, mothers, wives, children, sweethearts and all. The little village of Wall Hill never witnessed such a scene or had such a crowd before or since.

They left Wall Hill and walked to Holly Springs some 16 miles away, stayed the night in the homes of residents there, then took the train to Iuka the next day. In Iuka, they were made to haul their things about a mile out of town where they would camp outdoors. Their tents and equipment had not yet arrived and there was a big storm. I guess because it was too much to carry that night, the barrel of kraut that his father “had made” was left at the Iuka Depot. When LeGrand went back to retrieve it later, he found that,

“the hot July sun had caused my kraut to ferment and burst the barrel, and it was foaming and fixing, swelling and smelling. There was more cabbage than could have been crammed in a half dozen barrels with a compress, and such a stench! I never smelt anything to compare it to. I never claimed the cabbage.” (pg 24).

Although I have absolutely no evidence to support this idea, I like to imagine that the kraut explosion was the result of some enslaved person’s “passive” resistance to the Confederate cause. Someone was forced to make a barrel of kraut for the side fighting to preserve slavery, and that barrel exploded violently, spewing not only a massive amount of fermenting cabbage but also a great deal of horrible smelling gasses. A “kraut bomb,” if you will.

After two months playing soldiers at their camp in Iuka, LeGrand received word that

"the good people held a mass meeting at Wall Hill for the benefit of the Alcorn Rifles [the name of his troop], and readily made up a purse of $2,000 to purchase uniforms for the company (pg 30).

The soldiers took their measurements to send home to Wall Hill because “a committee of ladies and merchants had gone to Memphis to purchase the goods” (pg 31) to make the uniforms already.

As it turned out, LeGrand was selected to be the one sent back to Wall Hill to retrieve the uniforms while the rest of the soldiers began preparing to leave for Kentucky on orders. He took the train back to Holly Springs, arrived that night at 9pm, and from there hired a buggy and driver to take him the 18 miles or so west towards Wall Hill. He continues:

I still remember how eager I was to get on; how slow the horse seemed to travel, how often I admonished my driver to whip up. Slow or fast, a few minutes after 12 we turned into the lawn leading up to my father’s house, the dearest spot on earth to me. Desiring to slip in and not disturb my old father, and to surprise my wife, I drove around to the quarters to call one of the servants to look after the horse and driver, but when I reached the first door, and knocking called “Nelson,” my old nurse Rose knew my voice, and rushed out yelling like a Comanche: “Thar’s Mars. Jim! Thar’s Mars. Jim! I tole Miss Betty he was coming. I knowed he’d be home tonight!” and roused the whole camp, and before I could shake hands, give orders and reach the back door, Miss Betty and the old Patriarch were there to meet me. Home again! Good night!

Next morning we rode over to Brock’s Chapel, where we had been accustomed for years to meet with God’s people to worship. Now it was changed into a military workshop to manufacture clothing for Confederate soldiers. Six sewing machines occupied the altar. Two tables were erected upon the pews for the tailor who had volunteered to cut the clothing, and assist the ladies in making it up. The whole audience of twenty-five or more mothers, wives, and daughters were busy at work. When I walked into the dear old church, machines suddenly stopped, and a dozen cried out: “Where are the boys, Lieutenant?”.

They knew what my coming meant. They knew the boys had gone to the front. I had to talk to everyone, and answered a thousand questions to parents, wives and sweethearts, and this continued for a week, for a new set of hands came every morning to work, and the time passed rapidly and pleasantly. (Conf Sold pg 32-33)

I don’t know if enslaved women were working on these uniforms at Brock’s Chapel, but I assume this massive community-wide project would have affected everyone’s daily routine—including the enslaved community. LeGrand doesn’t say in the book whether he took any enslaved people with him to war, but we know that many white Confederates did this—forcing people they enslaved to be their servants in the camps between battles. In his other book, we learn that Isham and Elizabeth’s son George Adrian “Ady” who died in 1863 at Gettysburg had with him his “faithful servant, Stephen” who “sought for and carried his body off the battlefield, and back to the hospital, and prepared it for burial” (History, pg 43). Apparently, they buried Adrian in a coffin that Stephen had built. I have never heard more of this person named Stephen, where he came from, or where he went afterward. I think it’s possible that Stephen had been enslaved by the Wilsons and was “lent” out to Adrian since his mother Elizabeth had only Jerry and Nathan to help at the farm. Or, as white-revisionists have been known to do, Stephen could have been entirely made up to perpetuate the narrative that the slaves loved their masters very much.

Whether Stephen (or the story about him) is real or not, it does seem possible that some of people enslaved in Wall Hill would have been looking for information from LeGrand during this visit home about their family and friends who were forced to follow their enslavers to war.

In August of 1863, LeGrand returned home to Wall Hill again on furlough. This part of the county was apparently under the control of U.S. troops at that time. He writes some about what it felt like to visit “occupied territory” and what he saw there:

We were warned by the cavalry picket to look out for the enemy, but we felt like we were at home and looking out for friends and not our enemies; still we felt weary and did not enjoy our visit like we would have done, had we been within the Confederate lines. Friends came in to get letters from their boys in the army, and they told us to feel easy, that they would warn us if a cavalry raid was sent out from Memphis.

We found our country had been pretty well stripped by the enemy, and many people were living pretty hard, but we heard no grumbling, found the people as true as steel and hopeful of result. (Conf. Soldier pg 141)

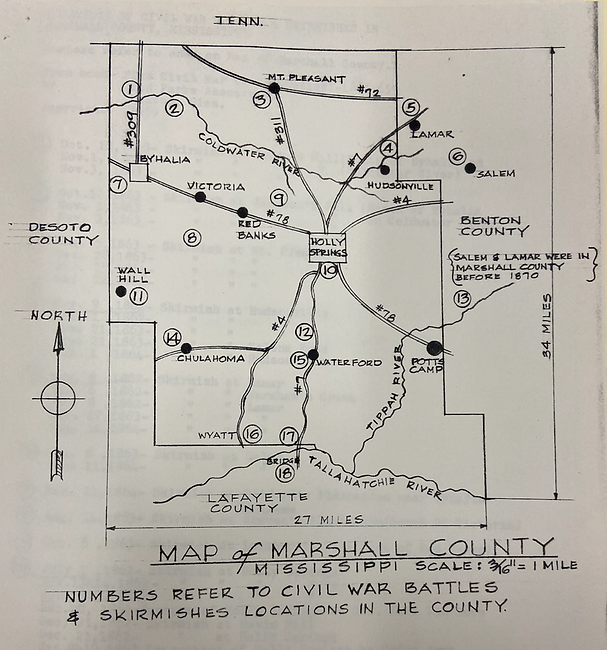

When talks of the place being “pretty well stripped by the enemy” I assume he is referring to instances when the U.S. troops would move into an area and commandeer anything they needed from the locals. There were a number of “skirmishes” in Marshall County which would have provided the opportunity for U.S. troops to come into contact with the general population. The following is a map and list of Civil War “skirmishes”—smaller battles—that took place in Marshall County from “The Civil War in Mississippi 1861-1865” by Ken Parks (1959). Notice there is a skirmish at Wall Hill in February 1864 and Chulahoma in November 1864.

-

Skirmish at Quinn’s Mill – Oct 12, 1863; Nov 1, 1863; Nov 3, 1863

-

Skirmish at Jackson’s Mill – Oct 12, 1863; Nov 1, 1863; Nov 3, 1863

-

Skirmish at Mt. Pleasant – Dec 28, 1863; Jan 25, 1864; May 22, 1864

-

Skirmish at Hudsonville – Nov 9, 1862; Dec 1, 1862; June 21, 1863; Feb 1, 1864

-

Skirmish at Lamar and Worsham’s creek – Nov 6, 1862; Nov 8, 1862; Dec 17, 1863; Aug 14, 1864

-

Skirmish at Salem – Oct 8, 1863; June 11, 1864

-

Skirmish at Raiford’s Plantation near Byhalia – Feb 11, 1864

-

Skirmish at Craven’s Plantation (south of Victoria) – Aug 14, 1863

-

Skirmish at Lockhart’s Mill (East of Red Banks) – Oct 6, 1863

-

At Holly Springs

-

Skirmishes July 1, 1862, Nov 13, 14, 28, 29, 1862

-

Capture of Holly Springs by Gen. Earl Van Dorn – Dec 20, 1862

-

Skirmish at Davis Mill and Holly Springs – Dec 21, 1862

-

Evacuation of Holly Springs by Union Army – Jan 9 & 10, 1863

-

Skirmishes near Holly Springs – June 16-17, 1863; Sep 7, 1863; Feb 12, 1864; Apr 17, 1864; Aug 1, 1864; Aug 27-28, 1864

-

11. Skirmish at Wall Hill – Feb 12, 1864

12. Skirmish at Lumpkin’s Mill – Nov 29, 1862

13. Skirmish at Tippah River (North of Potts Camp) – Feb 24, 1864

14. Skirmish at Chulahoma – Nov 30, 1862

15. Skirmish at Waterford – Nov 29, 1862

16. Skirmishes at Wyatt – Oct 13, 1863; Feb 13, 1864

17. Skirmish at Tallahatchie Bridge of the Mississippi Central Railroad – June 18, 1862; Aug 7-8, 1864

Grant's March Through Tyro

I found a brief personal narrative in the McAlexander collection at University of Mississippi that describes “Grant’s March Through Tyro”. The story seems to be written by a white person who recalls U.S. General Ulysses S. Grant coming through Tyro, MS when they were a small child. Tyro is only about 15 miles directly south of Wall Hill. If the U.S. Army did pass this way in 1863, I think the folks in Wall Hill would probably have known about it. Here’s what the author recalls:

After the siege and capture of Vicksburg, General Grant marched through Tyro and Holly Springs on his way to take possession of Memphis. Early that morning as Uncle Bob heard the tramp, tramp, tramp, of the approaching army, he came into our room and woke us from sleep. […] As General Grant headed the procession, he was the personification of a soldier. His coat was buttoned up in front with gold buttons, gold epaulettes hung from his shoulders and he was riding a high stepping bay horse whose harness was held together with gold buckles.

The author also recalls that their mother and other women of the community formed a “Lady’s Aid Society” to get supplies from Memphis to support the Confederate soldiers. Two of the women, including the author’s mother, took a covered wagon full of provisions for themselves, their driver “Uncle Bob” and the mules and a list of “things the boys of the neighborhood would need, ten or twelve in number”. They made it from Tyro to “Nonconnah Bottoms” about 8 miles south of Memphis where they stayed the night with a friend. That night, according to the story, Confederate Soldiers stopped at the house and were welcomed and fed and soon after, some Union troops arrived but did not cause any trouble to the family. The next day, they were able to get through the picket lines into Memphis and arrive at the woman’s brother’s home for the night. The next day, they began packing the goods that he had purchased for them to take back to Mississippi. The story says,

"...great fun was had as they packed the garments in the wagon. She put all she possibly could

under the spring seat of the wagon and covered them with the blankets which they called

their lap robes. She found no room for the two dozen hats. She had to think a few minutes.

“Here, Bob, I’ve found a place for the hats.” She packed one over the other very closely and

put them in the seat of Uncle Bob’s breeches, and a pretty pictures it made of him perched

up on his mule high above his saddle.

They spent another night with their friends in Nonconnah Bottoms and headed home the next day. I have no idea if there is any truth to this story at all, but if any is to be found, it’s possible that the folks at Wall Hill could have known about it. I have also entertained the idea that this is the trip during which the “committee of ladies […] had gone to Memphis to purchase the goods” (31) to make the uniforms that LeGrand would take back to his comrades in Iuka.

There are other (exaggerated, Lost Cause, “good ol’ days” of slavery) stories I could share told by white men and occasionally by white women about what was happening in Marshall County during the Civil War, but the above excerpts are all I know of that were told by people with a connection to the neighborhood where Nathan and his family would have been.

Van Dorn's Raid at Holly Springs

I don’t know for certain whether folks in Wall Hill would have known what was going on in the surrounding areas, but Holly Springs is only about 15 miles from the Wall Hill neighborhood so the war activity there surely would have had rippling effects in the surrounding countryside.

Among white slaveholders like Elizabeth Howze who had an interest in nearby military activities and successful campaigns launched by the Confederates, if there was one thing from the area that would have been widely known, I think that it would be Van Dorn’s raid on Holly Springs in 1862. The following are excerpts from the book "Ida: A Sword Among Lions: Ida B. Wells and the Campaign Against Lynching" by Paula Giddings.

Holly Springs was a strategic railroad hub in north Mississippi that changed hands fifty-seven times before the war’s end. In November of 1862, U.S. general Ulysses S. Grant along with thousands of troops came to Holly Springs and set up their headquarters. The town’s foundry had been sold to the Confederacy and was used to produce guns and the south’s first cannon earlier that year. (pg 22)

On December 20, the most spectacular battle that took place in Holly Springs was led by the Confederate general Earl Van Dorn, who had led his troops to the earlier defeat in Corinth. Under the cover of night, Van Dorn’s troops destroyed the Mississippi Railroad poised to aid Grant’s transportation to Vicksburg, detonated the piles of ammunition stored by the Union troops, and pierced the predawn darkness by setting the cotton bales and sutlers’ supplies afire. […] In the end, both the east and west sides of the central square and three blocks of buildings and the railroad station were destroyed. (page 21)

Aaron Jones, one of the “Ex-Slaves” interviewed by the WPA lived in Marshall County and he reported that he remembered the war, and that they could “hear the guns from the battle at Memphis and from Shiloh; and Van Dorn's Raid sounded like it was in our yard.”

After Van Dorn’s raid, Union soldiers retreated and “infantry columns subsisted off the food of Holly Springs residents and fanned out to strip a 370-mile swath of the northern Mississippi countryside of its corn, wheat, and livestock before burning plantations to the ground.” (Ida, 21). This—along with LeGrand Wilson’s recollection that Federal troops stripped his father of “everything in the shape of food” two or three times—certainly provides a basis for believing that the folks in Wall Hill might have experienced visits from soldiers during this period looking for resources.

"Ex-Slave" Narratives from Marshall County, Mississippi

While there are some questions about the methods used by the Works Progress Administration in collecting “Ex-Slave Narratives” in the early 1900s, we do see several stories from Marshall County. Some of the individuals recall raids and visits from soldiers during the war period. I have shared a few quotes below.

Emma Johnson

"I saw plenty of Yankees during the War. They took all Old Master's stock and killed the cows, hogs and chickens right in the field and brought them to the commissary in town.”

"They set the house on fire once, then locked the door and come out. The family was in the back of the house and they smelled smoke. They broke in the parlor door and found the fire and put it out.”

"General Van Dorn came to our house with some soldiers on the way to raid the Yankees in Holly Springs. He was a tall, sandy-headed man. I was too little to know what it was all about.

"And the next day, General Grant and his soldiers come to the house after they was run out of town. He was a heavy-set, blackheaded man.

"Yankee soldiers was foraging one day near our house and one of them was shot from the ambush and killed. I heard the shot and saw a soldier pick him up and carry him off on his horse.”

Aaron Jones

“We saw plenty of Yankees then, because they scattered all over the country. They use to come on our place and kill a calf or a pig with their bayonets and drag it off. They stold chickens and turkeys too. They persuaded Porter, one of the ni--rs to go North with them and he never was heard from again."

Callie Gray

"The Yankees stole the corn and wheat and drove off the horses and mules and killed the hogs and sheep, and took all the chickens, but we sho saved the turkeys. We could hear the Yankees coming, and we dropped corn under a old house and when the turkeys all wus under the house, we nailed planks 'round the bottom. Then we swept away all the tracks. Yes, we sho saved the turkeys.

Henry Walton

“The Yankees tried to burn the house and did run off all the stock and take all the vitals, and we had nothing much to eat.”

I wish that we could know what Nathan and his family members thought of these visits, and how they managed to balance both their enslaver’s expectations of their behavior, and their own feelings about the war, their family’s safety, and their visions of the future. I wonder what they thought and how they would have responded to learning about Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 which declared their freedom and announced that they would be accepted into military service for the United States.

United States "Colored Troops"

Mississippi was a Black soldier recruitment hub for the Union Army, and most of the regiments were organized after the surrender of Vicksburg on July 4, 1863 (Giambrone, 82). Of the 200,000 plus Black soldiers that fought for the Union army, 17,869 of them were from Mississippi (Giambrone 82-83). But as early as August of 1862, Black Americans that escaped slavery could "join" the union army although it was mainly limted to menial jobs rather than combat roles. The Black soldiers would have faced prejudice from the white soldiers, and dangerous if not deadly consequences if they were captured by the Confederates.

In January of 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation made it official that Black Americans could join the armed services. In March of 1863, the US Army began organizing "contraband camps" at abandoned plantations across the south as a way of recruiting new soldiers among the enslaved community. The "Bureau of Colored Troops" was official established in May of 1863.

Running away from your enslaver and finding your way to one of these "contraband camps" was one way to join the American cause, but there was another way to join as well. In Wall Hill, MS and many other southern towns, Union Soldiers would often go out on "scouting missions" or would be directed to confront the Confederates in smaller battles (or "skirmishes" as they are called above). If the Union soldiers were successful, they might take resources, food, weapons, or other propert--including those enslaved by the enemy--back to their headquarters. This is exactly what happend in Wall Hill in May-June of 1863.

In a book titled "Supplement to the Offical Records of the Union and Confederate Armies; Part 2- Record of Events, Volume 19, Serial No. 31" we find some very interesting details about what happened. Here is an excerpt from pages 140-141:

"Stationed at La Grange, Tennessee, May-June 1863

May 11-15 -- Engaged in a scout to Senatobia, Mississippi and returned May 15. Engaged the enemy while on picket duty near Looxahoma. Repulsed them, killing one and wounding two; our loss nothing. Fell back and pursuit ensued and a skirmish near Wall Hill with no definite result on either side. Fruits of this scout: 450 horses and mules and 300 Negroes; distance traveled 225 miles."

I believe that Rev. Alcorn's cousin Charlotte and husband Joe Lucas (later Hancock) and others from Wall Hill might have been among the 300 "Negroes" that the Union soldiers emancipated and brought back with them to La Grange, Tennessee.

Nathan would have been about 35 years old in 1863 and his brother Jerry, about 40. Their oldest sons (of those we know about) would have been around 10 years old at that time. I know that Jerry and his family are in Wall Hill immediately following the war and at least until the 1890s.

In 1870, Nathan and his family are living just a little north and west of Holly Springs. I am not sure if there was a "contraband camp" near there, but my hunch is that Nathan went there because his wife Ella might have been enslaved by Charles Yarborough whose plantation was near there.

In all the USCT records, I could find only one reference to a Nathan House. I don’t think this is the same Nathan whose steps we’ve been tracing, because this Nathan House mustered in the 58th Regiment at Natchez, Mississippi which is 300 miles south of Wall Hill. I suppose it’s possible that he went that far, but I really have no way of knowing. My hunch is that he did not join the USCT.

Joe and Charlotte Lucas, however, are living in La Grange, TN in 1870. I think Joe joined the USCT at La Grange.

The following individuals mustered in during the summer of 1863 at LaGrange, Tennessee as the 2nd Tennessee Volunteer Infantry (African Descent). There were many individuals that served in this group, but I couldn’t help but notice the following names:

James Hill and Thomas Hill – possible children of Henry and Milly Hill. They would have been in

their late teens and early twenties at this time.

Joseph Hancock – I believe this is Joe Lucas, husband of Charlotte who goes by “Joseph Hancock” later in his life. Joe would have been about 35 years old at this time.

Peter House – possible child of Nancy, brother of Charlotte, Fanny and others. Peter would have

been in his mid-thirties at this time

George House – possible husband of Fanny who would have been around 20 years old at that

time.

The 2nd TN Volunteer Infantry was charged with garrison and guard duties in the area around La Grange and in Memphis. They also successfully defeated a Confederate cavalry that was attempting to burn down a railroad bridge over the Wolf River near Collierville. The regiment was re-organized on March 11, 1864, in Memphis, and re-designated the 61st United States Colored Infantry.

If any of these folks were friends or family of Nathan and the others from Wall Hill, they would have passed through Collierville a lot during their time in the military. Collierville was occupied by U.S. troops for the entire Civil War period. It is not hard to imagine that Joseph Hancock mustered at LaGrange in 1863 after he and his family left Wall Hill with the Union soldiers during the scouting trip in May 1863. I think that is why we find Joe and Charlotte in Fayette County in 1870 and 1880, then Collierville in 1900 and 1910.

The End of the Civil War

The beginning of the end of the Civil War happened in April 1865 when Confederate general, Robert E. Lee surrendered, which led to a wave of surrenders and ultimately the official end of the war. Abraham Lincoln was assassinated in April of 1865 too, and I’m sure that news spread quickly even down to our rural village in Marshall County, Mississippi. Did Nathan and the others celebrate the end of the war? Did they mourn the death of Lincoln? We can only guess.

LeGrand J. Wilson gives a very sanitized summary of what his father did at the end of the war. Elizabeth Howze may have done similarly, following the lead of her father. I do not know. This narrative is interesting because it’s specific to Wall Hill, but also problematic because of when it was written, and by whom. He writes:

The surrender of the Southern armies was about over by the 1st of May. My father’s crop

was about planted, and he planted more than he had done for two or three years. About

the 15th of May he called all the negroes up, and told them they were free, and could go,

if they desired, and find homes for themselves and make their own contracts for the year.

They were astonished and speechless. After waiting for them to speak, my father said,

“All who desire to go, rise to your feet.” Not one moved. Father said, “Now, I will make

you a proposition. If you go on as you have begun, cultivate and gather the crop, as you

have always done, obey order, and behave yourselves, I will feed and clothe you as I have

always done, and if the crop pays expenses, and there is anything over, I will divide

among you. The old home will be broken up this fall. I can’t live by myself, I will try to

rent the land, as it is impossible to sell it.”

“Thankee, Master, we will do our best,” came from all sides, and the conference ended.

The year 1865 was more than an average crop year, and everything produced well, but provisions were so high and scarce that it did not more than pay out. The corn used in cultivating the crop cost more than one dollar per bushel; middling meat 33 1-3 cents per pound, and everything else in proportion.

The time came to break up the old home. It was a very sad day! The negroes had made their contracts for another year, and started away in tears. Summer, an old man now, came to me and said, “Mass Jim, I want to go wid you.” “All right, Uncle Summer, I will do the best I can for you.” Taking my father and Summer, we started for my home at Tyro, bidding the old home farewell!

I could never find out where Nathan and the others were in 1866 while Jerry, Solomon, Aggy, and Grace were with Elizabeth Howze. If Elizabeth did what her father did and offered everyone the option to stay and work or leave and make their own contracts, I guess Jerry chose to stay for a little while.

In 1875, just 10 years after the close of the Civil War, Jerry is still working the land where he had previously been enslaved. By then Isham and Elizabeth were both dead, and their son Henry Legrand Howze owned the property. Their daughter "Donnie" Howze was living next door to her parent's property with her husband J.T. Eason. Here is an excerpt from a deed recorded in Marshall County that year between Jerry Howze and J.T. Eason (blanks are in place of words I could not decipher):

Whereas I am indebted to J.T. Eason __ in the sum of one hundred thirty one __two dollars, a balance due for dry goods, groceries, plantation supplies __ ______ by the said J.T. Eason _ for the year 1874 as evidenced by my note for said amount of ___ date ___, and due and payable on the 1st day of Oct. 1875. And whereas the said J. T. Eason __ has agreed to furnish me during the year 1875 with dry goods, groceries, plantation supplies so to the amount not to exceed two hundred dollars, said last named sum to be due and payable on the 10th day of January 1876. And whereas I am anxious to secure the payment at maturing of said indebtedness, now therefore in consideration of the ___ and the sum of Five dollars to me in hand paid, the receipt of which is hereby acknowledged I have this day granted, bargained, sold and do by __ ____ grant, bargain, sell and coveny to J.T. Eason __ the entire crop of cotton, corn, fodder, and all agricultural products made by me or under me during the year 1875. Said crop to be grown on the plantation in Marshall County, State of Mississippi owned by Henry L. Howze and meted and corded by me.

I also hereby bargain, sell and convey to J.T. Eason __ 1 (one) Bayhorse 12 years old. One mouse colored mare mule, 10 years old, and one (1) two-horse wagon and the title to the same. I warrant and defend unto the said J.T. Eason __ _should I fully pay off and discharge the whole of said indebtedness to him before mentioned when due ___ this conveyance to ____ and of no effect, but should I fail to to pay said indebtedness on any part unto ___ ___ ___ some feels __, thus and in that want unto said A. H. Christopher is to take possession of the property heretofore mentioned and after ____ the time, place, and terms of sale for the period of time __ of notice parted of them or nonpublic place in said county, he to sell the same to the highest bidder for cash and apply the proceeds to the payment of the cost of sale and said indebtedness. The surplus, if any ____ to be dispersed of according to law. Witness my hand seal this 25th day of February 1875.

Jerry Howze (seal)